|

from The Worldview Literacy Book copyright 2009 back to worldview theme #16 |

| Discussion Morality and ethics are concerned with

right and wrong ways to behave. One

such way is to, always, above all else, look out for one's self

interest. Its opposite,

altruism, places the interests,

welfare, happiness, and perhaps even survival of other people or living

things above one’s own interests. Michael Shermer, in his 2004 book The

Science of Good and Evil, characterizes religion as "a social

institution that evolved as an integral mechanism of human culture to

encourage altruism and reciprocal altruism, to discourage selfishness

and greed, and to reveal the level of commitment to cooperate and

reciprocate among members of the community."

Generally present in some form in all major religions and in

cultural heritages throughout the world, is a behavioral recipe known as

"The Golden Rule." (See Figure #16a.) English philosopher John Locke described

this (in 1690) as an "unshaken rule of morality, and foundation of

all social virtue." The

positive version, stated in the above worldview theme description in one

variation, was part of Jesus' Sermon on the Mount.

Confucius, in the 6th

century BCE, is generally credited with the negative version of this

universal principle: "Do not do unto others what thou wouldst not

they should do unto you." The

Jewish sage Hillel provided a slightly different version in 30 BCE:

"What is hateful to you, do not to your neighbor."

In comparing both versions,

ethicists generally prefer the negative formulation, for, as philosophy

professor Steven M. Cahn puts it, "It does not imply that we have

innumerable duties toward everyone else." About that negative formulation Cahn goes on to say,

"[it] is not the supreme moral principle since it does not prohibit

actions that ought to be prohibited."

He suggests that, by following it, a masochist might inflict pain

on others. In similarly

finding fault with the Golden Rule, another asked, "How would you

feel if a million Soviet troops stormed your Reich capital?" While not perfect, in the search for a concise, easily

understood supreme moral principle, the Golden Rule is one of the best

choices. (See worldview

theme #42 "Ethical Orientation" for some other ones.)

Why do some people often behave altruistically, while others

rarely or never do? In analyzing research on the evolution of moral behavior by

anthropologist Donald E. Brown, Shermer

identified twenty-nine traits that "contribute to a behavioral

expression of the Golden Rule." Included in this list are fairness, cooperation,

co-operative labor, food sharing, hospitality, promise, reciprocal

exchanges, turn taking, and

empathy. Empathy—"fellow

feeling" or imagining that you are in the other person’s shoes

and experiencing his or her feelings, struggles, etc.—is one of the

more important pre-requisite traits in this list.

Emotionally immature people, in particular those who after

experiencing so much pain as children have learned

how to block it, may not feel compassion for

|

Discussion—continued others' pain.

Many believe childhood experience and genetic endowment basically

wire neural connections in the brain and play a key role in one's

ability to empathize. After

studying mirror neurons, some neuroscientists believe empathy can

specifically be traced to neural networks with mirror properties.

The Golden Rule is a simple recipe for human behavior. Another

equally recognizable one from human history is embodied in "an eye

for an eye, a tooth for a tooth."

Together these provide the following prescription for moral

behavior: "You should cooperate first.

If others cooperate continue to do so. If someone defects, you

should defect in similar fashion. But if they start cooperating again,

you should also." Interestingly

enough, this is basically the TIT

for TAT strategy—a computer program of interest to political

scientists, those studying human nature, and the evolution of ethical

behavior. This program achieved such success in tournaments involving

non-zero sum "cooperate/defect" games, that some speculate its

mental equivalent was important in the evolution of cooperation.

A winning strategy is defecting on the last move: if

you plan on never seeing someone again, you cheat or behave badly!

Human nature may require distinguishing "insiders and

outsiders"—those you treat right and those you don't.

As a 2007 Time article "What Makes Us Moral"

reports, "This kind of brutal line between insiders and outsiders

is evident everywhere." Its

existence is no surprise—sociologists

made a similar community vs. society distinction in the late 19th

century. How

distinguishing "insiders and outsiders" and ethical behavior

evolved in humans over a long period of time can be described using a

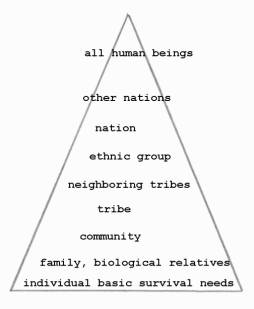

pyramid. (See Figure #16c.)

When people were little more than animals their behavior was dictated by

self interest in meeting basic survival needs—shown at the pyramid's

base. Among

pre-civilization humans, ethical behavior extended to include family and

biological relatives. As

culture developed and survival pressures eased, ethical behavior was

extended greatly, moving up the pyramid, to eventually include

community, tribe, regional neighbors, ethnic group, and nation. Today, at the top of the pyramid, are those who feel a

sense of belonging to the whole human species and behave accordingly.

Use of the phrase "all human beings" in the opening

sentence of the statement of this "Golden Rule..." worldview

theme connects those who value it with those at the pyramid's top. For many a "Village Ethic of Mutual

Help" is logically part of the Golden Rule—it

was for David Starr Jordan. In

his 1894 book The Factors in Organic Evolution, he saw a weaker

ethic "Live and Let Live" being strengthened with a "Law

of Mutual Help" to become "Live and Help Live."

For Jordan, this was a simple way of describing the jump from the

Silver Rule to the Golden Rule. Besides

mutual help, inherent to worldview theme #16 is Good Samaritan type

behavior (Figure #16b). Behaving this way requires extending trust to

complete strangers. |

|

Figure

#16a

Figure #16b Parable of the Good Samaritan [He]

said to Jesus, "And who is my neighbor?" Jesus replied,

"A man fell victim to robbers as he went down from Jerusalem to

Jericho. They stripped and

beat him and went off leaving him half-dead.

A priest happened to be going down that road, but when he saw

him, he passed by on the opposite side.

Likewise a Levite came to the place, and when he saw him, he

passed by on the opposite side. But

a Samaritan traveler who came upon him was moved with compassion at the

sight. He approached the

victim, poured oil and wine over his wounds and bandaged them.

Then he lifted him up on his own animal, took him to an inn and

cared for him. The next day he took out two silver coins and gave them to

the innkeeper with the instruction, 'Take care of him. If you spend more than what I have given you, I shall repay

you on my way back.' Which

of these three, in

your

opinion, was neighbor to the robbers' victim?"

He answered, "The one who treated him with mercy."

Jesus said to him, "Go and do likewise."

—from

the Bible, book of Luke 10: 29--37 |

Figure #16c Ethical

Behavior Evolutionary Pyramid

|