|

from The Worldview Literacy Book copyright 2009 back to worldview theme #10 |

|

Discussion

Theology, the rational study of religious faith, experience, and

practice, traditionally considers three arguments for God's

existence: 1)

cosmological—assuming that every event has a cause, one looks back for

causes behind events to the first event: the beginning of the universe.

This "first cause" is linked to God,

2) ontological—based on defining God as a perfect being,

realizing that such perfection requires God be complete and lack no

attributes, certainly God exists! and 3) teleological —given obvious

evidence of design in the universe, it must have had a designer.

William Paley (1743-1805) provided the famous watch/watchmaker

analogy often used here.

Secular Humanists are not convinced by any of them.

They appeal to "Scientific Materialism" (worldview

theme #5A) for help in demolishing the last one—the one that looks to

empirical evidence—to show God could be a "blind watchmaker"

and is not needed. The

phrase serves as the title of a classic book written by evolutionary biologist and atheist Richard Dawkins.

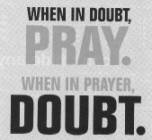

In his 2006 book, The God Delusion, Dawkins argues that

religion is dangerous because it leads people to choose faith in God

over reason—a choice which he sees as a first step down a

"slippery slope" to hate and violence. Skeptics have long used the widespread presence of

such evil to question God's existence by asking (and stating the problem

of evil), "Why does an all

powerful, all knowing God allow evil to exist in the world?"

Without religious faith to give

their lives meaning and them a sense of belonging, secular humanists

must look elsewhere for these. Otherwise

they are faced with a meaningless life, emptiness, and what

existentialists call the anxiety of nothingness.

In this regard consider the Greek myth of Sisyphus—who

pushes a heavy stone up a steep hill, only to have it roll back down.

He is punished by the gods and forced to continually and forever

repeat this task. Is he

attempting to build something that will last, perhaps a temple?

Does he become reconciled to his plight and eventually accept it?

In The End of Faith, atheist Sam Harris's arguments

suggest that metaphorically people like Sisyphus believe they have been

promised immortality in exchange for their toil.

He writes, "What one believes happens after death dictates

much of what one believes about life, and this is why faith-based

religion...does such heavy lifting for those who fall under its

power."

Humanists meet this "meaningless life" challenge by

seeking to (in the words of a statement from the American Humanist

Association) derive "the goals of life from human needs and

interest rather than from theological or ideological abstractions."

They look for values in "human nature, experience, and

culture" and to each other and the natural world in seeking to meet

belongingness needs. Beside

the responsibility to put meaning into a seemingly irrational world with

no discernible purpose, secular humanists feel (in the words of the AHA

state-

|

Discussion—continued ment)

"humanity must take responsibility for its own destiny."

Put another way, in casting off

"God, our Father who art in Heaven," secular humanists

believe humanity is serving notice that its childhood has ended.

It has come of age and grown up.

In seeking answers to the adult problems it faces, they urge

humanity to be (in the words of the AHA statement) "informed by

science, inspired by art, and motivated by compassion."

While embracing reason and freeing themselves of supernatural,

mystical elements, secular humanists still have feelings and perhaps

even spiritual needs. What

they call spirituality might be better described as (in the words of

Jaron Lanier) "the range of one's emotional relationships to those

questions that cannot be answered."

These are the big questions like "What is the nature of

Reality?" "Why am I here?"

"What is really worth caring about?"

Their response to this last question may be twofold: 1)

"each other" and 2) "our home planet."

The AHA statement extends this by seeing humanism as

"affirming the dignity of each human being" and supporting

"the maximization of individual liberty and opportunity consonant

with social and planetary responsibility."

Rather than being overly concerned with finding salvation in an

imagined world to come, secular humanists are grounded in the reality of

this world. They do dream

of making it into something better—a

sustainable, pluralistic, tolerant society of self actualized

individuals built on a foundation of equal educational opportunity,

participatory democracy, valuing human rights, and social justice.

While secular humanists (with help from the American Civil

Liberties Union) are often behind efforts to maintain separation of

church and state in American society, in describing how people ideally

ought to treat each other, they like to borrow from the wisdom of the

world's great religions. In

doing so they often promote brotherhood and the Golden Rule (see

worldview theme #16). Some

embrace organized religion: affirming principles of Unitarian

Universalism (Figure #10) seems increasingly popular.

Many humanists concerned about the future feel faith-based

religion presents humanity with big problems and big challenges.

These might be summarized by asking, "How can what is good

about traditional religion be preserved and what is wrong be slowly

weeded out?" System thinkers (theme #13), who like to imagine a desired

future and then work to design a system that behaves as desired, face a

challenge in thus trans-forming a generic traditional religions'

conceptual framework viewed as a system (see figure, page 14) into

something better. It is

possible to imagine new religions in a secular humanistic future.

Carl Sagan described one, writing, "A

religion that stressed the magnificence of the universe as revealed by

modern science might be able to draw forth reserves of reverence and awe

hardly tapped by traditional faiths." |

|

Figure #10: Unitarian Universalist Perspective Discussion

Between Eric, age 7 and his Dad Eric:

Dad, what happens to us after we die?

Is there a heaven? Dad:

Well, some people believe that after we die we go to heaven where we

live forever, and other people believe that when we die, our life is

over and we live on through the memories of people who have known us and

loved us. Eric:

What do you believe? Dad:

Well, some people believe that after we die we go to heaven, and other

people believe... Eric:

But what do you believe? Dad:

OK. I believe that when we die we live on through other people but not

in heaven. Eric

(after a long pause): I'll believe what you believe for now, and when I

grow up I'll make up my own mind.

Adapted from "Home

Grown Unitarian Universalism"

|

from

UU advertisement, spring 2008 |