|

from The Worldview Literacy Book copyright 2009 back to worldview theme(s) #18 |

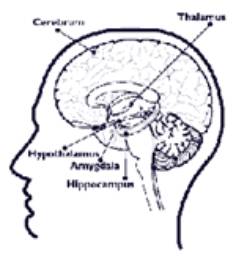

| Discussion #18A: Acting on impulse means responding immediately to

a triggering stimulus with little or no conscious control or direction.

Most fundamentally, our brains—and those of all animals—are

structured to do this in response to danger.

We have an "alarm system" (centered in the amygdala,

part of the limbic system, Figure #18b) that can instantly prepare our

bodies for fight, flight, or (less dramatic) appeasement responses.

A quarter second or so later, the brain's cortex can evaluate the

alarm it receives, put it into context with other information, and more

consciously, rationally decide whether to activate a full blown survival

type response, or to dampen those preparations.

Indeed, our most

basic instincts—and most powerful emotions like anger and fear—can

operate without the conscious mind intervening.

In non-emergency situations such emotions are held in check by

the higher functions of the brain—regulation which works better in

some than in others. Some

suffer from impulsive behavior disorder—especially dangerous for those

unable to resist temptation to engage in behavior known to be risky or

harmful. The behavior of teenagers is of concern in this regard.

Since prefrontal lobes aren't fully developed until a person

reaches his or her mid-twenties. It's

been speculated that young brains are directed more by the limbic system

than they eventually will be. (The

cortex will assert itself as they age.)

Studies suggest that children who resist instant gratification

and are able to delay rewards have better adult lives.

Researchers have long hypothesized a link between

neurotransmitters—the chemicals released as the cells responsible for

brain activity (neurons) fire—and human personality types. Robert

Cloninger has suggested that the brains of extroverted individuals high

in "novelty seeking" (described as quick-tempered, curious,

easily bored, and impulsive) rely more on the dopamine behavioral

activation system than other neurotransmitter modulated behavioral

systems. While this has not

been demonstrated, research does suggest that how our brains respond to

environmental stimuli is more dependent upon personality than once

thought. It suggests that,

to the extent to which a person is extroverted or neurotic, his or her

brain will amplify certain experiences over others. #18B: Like

our "fight or flight" reaction to danger, many basic bodily

functions, needs and urges can be met without the conscious mind's

intervention—rather they involve unconscious, automatic responses to

environmental stimuli. For

example, if the hypothalamus in

your brain's limbic system indicates a "hungry" condition,

upon seeing food you will automatically eat—unless conscious, higher

brain functioning suppresses this urge.

(Perhaps you're on a diet!)

How much of what we do is the result of conscious,

deliberate decisions and how much originates in unconscious automatic

directives? Research |

Discussion—continued suggests that generally the contribution of the

unconscious component of our behavior is greater than was once

thought—but again this seems to vary with personality.

Some people are much better at suppressing urges, deferring

gratification and patiently waiting as necessary to carry out plans

they've formulated to meet goals—plans with subgoals and sub-subgoals.

David Stephens, University of Minnesota Professor of Ecology, has

studied animals "discounting the future"—

doing or consuming something now, rather than waiting.

He believes animals have "a

hardwired rule that says, 'Don't look too far in the future.'

Recognizing humans are physically not much different from their

ancestors—foragers who were not penalized for taking resources

impulsively —Stephens thinks he understands why many people have such

difficulty suppressing their "have it now" urges. Human ability to control emotions like

anger varies greatly. A few

become so

violently out of control that their passionate rage leads to murder! Reportedly one in three murderers claim they remember

nothing of their crime. Some

neuroscientists accept this and say it fits their belief that the

killers weren't really there: their conscious mind was absent when they

killed! Some better control

letting their emotions out: expressing anger constructively, being

objective, blaming or not blaming others as appropriate.

Still more "dispassionate" are those who fit the ideal espoused by ancient stoic

philosophers. They taught

the importance of self-control, reason, and courage in maintaining clear

judgment—especially during tumultuous times when one might otherwise

succumb to destructive emotions. In

general, stoics seek to maintain inner calm, have their lives flow

smoothly and evenly. Like

Buddhists, they believe life is potentially full of suffering brought on

by passions and desires. They

believe that removing these—especially distress, fear, lust, and delight—is

the key to having freedom. Figure

#18a: Stoic

Serenity

|

|

Figure

#18c

back to worldview theme(s) #18

|